Charting a New Course for Youth Engagement

A blueprint for how using strategic inquiry can help your nonprofit better understand your community’s needs and provide key insights with the potential to help you innovate and better serve those who count on you.

Make sure your nonprofit isn’t reproducing the same inequalities your mission has set out to eradicate.

It is so easy to maintain the status quo in organizations, to “keep on keeping on” even as the very ground shifts beneath us. But every organization can benefit from using inquiry to think more strategically about how to serve its mission.

In the Fall of 2022, the Decatur Education Foundation, which I had the privilege to lead for 14 years, launched a year-long strategic inquiry process to reshape our approach to serving youth. This initiative detailed in my earlier article, “How to Implement Strategic Inquiry at Your Nonprofit in 5 Steps,” aimed to thoroughly understand young constituents’ needs, delve into pertinent research, and draw inspiration from innovative strategies in our field. I now share the key insights that have the potential to transform not only our organization but also offer a blueprint for other nonprofits, particularly youth-focused organizations, seeking to innovate and better serve their communities. This piece will discuss the critical findings from our research, the strategic decisions made for the future, and the invaluable lessons learned about fostering a culture that truly understands and empowers youth.

Why Strategic Inquiry?

It is so easy to maintain the status quo in organizations, to “keep on keeping on” even as the very ground shifts beneath us. But every organization can benefit from using inquiry to think more strategically about how to serve its mission. By the conclusion of my year, I learned not only about how to better serve youth but also about the incredible value of strategic inquiry to provide a foundation for thinking outside of the box.

During this year-long inquiry, I identified five key findings which I presented to the organization’s board and staff in the spring of 2023. During that time, I also wrapped up my leadership at the organization but was able to leave a comprehensive report that analyzed these findings to help my successor make critical decisions about DEF’s future.

What We’ve Been Waiting for—The Findings

While DEF and my research focused on youth-serving nonprofits, the key takeaways can be applied to a variety of human service organizations. It is my hope that these findings inspire other organizations to take time to really look at how they work with their key stakeholders. Let’s get curious about how we can all build organizations with cultures of connection and collaboration!

Finding 1: Spaces bring people together.

During our research, one of the key findings we kept coming back to was that youth spaces outside of school serve a critical role in development. This is especially the case for the numerous students who don’t find connection points either in the classroom or school-based extracurriculars.

When I spoke to a student at a Washington teen café called The Garage, they reflected that they felt greater connection at this space than at school: “[At The Garage,] they remember your name. They actually care about, like, what goes on their environment. They actually care about the people that come here.” This sentiment was echoed at the Ann Arbor youth-driven teen center, the Neutral Zone; a youth who identified non-binary and on the autism spectrum explained, “I don’t have a lot of spaces that feel welcoming, and when I came to Neutral Zone, I felt a shift. I felt like I could breathe and have meaningful relationships with adults. I am very selective about where I share my full self.” Over and again, I saw how local youth spaces provided community, especially for kids who were not part of traditional school activities.

As such, I recommended that DEF explore whether a stand-alone youth space would be feasible in our community. This would undoubtedly involve collaboration with several partners with whom we already had strong relationships, including the city of Decatur, local businesses, and commercial real estate companies. After all, even if DEF couldn’t single-handedly fund and run a youth space, the organization had strong community ties that could turn this idea into a reality.

Thinking about shared and accessible spaces brings up interesting questions that can be applied more broadly at other types of nonprofits. Ask yourself: Does your agency have communal spaces for the population you serve? We know that shared communal spaces help youth build community, but what about expectant mothers, seniors, or refugees? Who doesn’t benefit from more places to build community?

But wait—before you start sketching out a plan to knock down the office next door and turn it into a playroom (we can all dream, right), check to see if there are other organizations you might partner with who already offer this. It might be as simple as sending your clients[1] in the right direction. And if you can’t find anyone who already has a space on offer, consider what steps (however small) your organization could take to create a space for those you serve. This could be as simple as making your office or service location more welcoming or offering a few shaded chairs outside where your clients can sit and chat together (weather and local laws permitting, of course). As you talk through this possibility, you might decide it makes sense to survey or engage those you serve to see if (and what kind of) a space might add value by creating connection and community.[2]

Finding 2: Staff-client interactions built on mutual respect and trust create a culture of belonging.

It makes sense: the way adults interact with youth is critical to creating a youth-centered culture. When I visited innovative youth-centered programs, I found that the underlying assumptions about youth were vastly different from what is typically seen in schools. Whereas schools tend to be hierarchical institutions with a significant power differential between adults and youth, youth-centered organizations pay particular attention to building trust with youth, leading to more authentic engagement.

At DEF, I recommended we promote and fund youth-centered training for adults and youth. We piloted this through our partnership with VOX ATL, which taught us how to begin to unlearn adultism. That is, this partnership underscored how giving youth voice and power requires training and intention.

We have reached a time where there is a growing awareness that top-down philanthropy just doesn’t work. Social justice work has to be grounded in relationship.[3] For your nonprofit, take a look at all aspects of your community engagement. Approaching the community you serve with a holistic mindset for their engagement can help you identify where your culture is out-of-sync with your community. All too often organizations are so busy doing the work that they forget to stop and think about HOW they are engaging with constituents. Make sure you are not reproducing the same inequalities your mission has set out to eradicate.

Consider whether your organization could use training and support to build connection and trust with the communities you serve. Are there organizations in your sector who might provide models that you could learn from? Remember, trust is built slowly over time, so this needs to be baked into your culture. Often, being transparent about mistakes in the past—and how things will be different moving forward—is the first step toward building those strong relationships with your community.

And trust starts with the leader of the organization—how we act with staff and clients. Some of the ways we build trust are simple: we get trust by giving it, trusting staff with decision-making and giving them the flexibility to do their best work (i.e., not burning them out). Building a culture of trust requires you, as the leader, to be vulnerable and cede control.[4]

Finding 3: Value lived experience as much as learned experience.

So often, we undervalue (either inadvertently or intentionally) the time and experience of our clients in helping us do our work. We are trained to value learned experience—no one questions, for example, the remuneration paid to consultants for their knowledge. However, we often put less value on lived experience, expecting people to participate in focus groups and input meetings for free. But this feedback is crucial to the success of our missions and should be compensated as such.

We learned that the top youth-centered organizations compensate youth for their time and expertise. During our partnership with VOX ATL, we built in the cost of paying youth for their input as well as for their work in helping to develop and facilitate our programming.

Ensure your organization makes it a priority to compensate your clients for sharing the expertise gained from their lived experience. This could be with money or gift cards, as well as providing supports like childcare and food. If you are funded by outside grants, make it clear that this compensation represents an essential part of the budget—a critical cost that needs funding, not something that “would be nice to have.”

Finding 4: Avoid tokenization at all costs.

Seeking input from the lived experience of those you serve comes with a risk: namely, that of tokenizing input. This is something to avoid at all costs. In our research, we found that having “tokenized” youth input is just as bad or worse than having no input from youth. Think about it: in a school setting, youth are often asked to complete surveys and then nothing is done with the information—or, at the very least, they don’t see anything being done with that information.

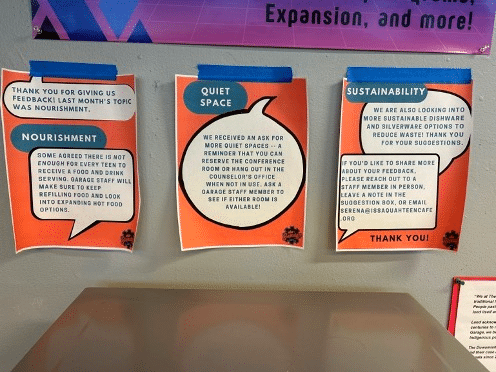

Let’s contrast this with what I found when I visited that teen café, The Garage: their walls featured youth feedback as well as answers to that feedback. If you look at the middle bubble, “quiet space,” you’ll see that the organization was already providing what was requested but may not have clearly communicated it; instead of ignoring the feedback, they posted a reminder. In the other two signs, they note that they are currently working on making sure there’s enough food to go around and researching more eco-friendly dishware. By publicly posting the feedback and response, it is clear that they not only received the feedback but planned to do something about it.

While we can’t always implement what our clients tell us they want, it is disrespectful to ask for their input and then go on with business as usual. So often, organizations seek input from the people they serve and either don’t review it with any intentionality OR they review it, decide that they can’t implement the suggestion but never circle back to explain.

When we are truly in community with those we serve, the feedback loop should be two-way. Circling back to your clients after asking for their ideas demonstrates that you value their expertise and builds trust. You might even consider taking it one step further and look at ways to include your clients in decision-making.[5] I’ve found the best ideas can come from this process of continual feedback—as long as there’s an environment of trust and respect.

Finding 5: Efficiency isn’t everything.

Being a youth-centered organization and running youth-driven programming takes a lot of time and effort. This can be a challenge for organizations that are short on staff and always feeling under pressure to get results.

In reality, it is not always convenient for staff and board members to engage meaningfully with youth or put youth in decision-making roles. The practical hassles often add up: meetings and events have to take place in the evenings or weekends, not during work days, and they might take much longer. But both VOX ATL and the Neutral Zone have decided to forego efficiency in order to center youth engagement: both organizations pre-meet with youth to be sure they feel prepared and supported for each meeting, meaning that there is always another meeting before the big meeting. This requires a change in mindset from one focused on efficiency and moving quickly to one that prioritizes all voices, power-sharing, and comfort over speed.

Of course, most organizations have a limited amount of both time and money, so committing fully to co-creating a collaborative client-focused culture may mean you have to give up something else. Think about your programming or events: are there any that feel more like box-checking? What can you let go of to move towards a more holistic model? To best answer these questions, you might have to check in with your clients. Again, this might not feel the most immediately efficient, but at the end of the day, creating client-focused services is the best way to serve your community.

Systemic Problems Require Systemic Solutions

When I began the Year of Strategic Inquiry, I did it without really knowing what I was looking for. At the root of it, I wanted to think more deeply about serving youth in a way that felt intentional and authentic. I knew that our organization could do better.

When I think about these five findings that resulted from that year, I realize that they are interdependent. That is, they demonstrate that systemic problems can’t be solved in a vacuum; instead, they require systemic and holistic solutions. Having a space for youth to gather, for example, isn’t enough if the adults are not trained in power-sharing and collaborative decision-making. After all, without intentional focus on building trust, youth would eventually stop coming to a space.

Each of these findings is a building block towards building a community-centered culture. And the ground that these are built on is inquiry.

Sources

[1] A note on this usage of the word, “client”: Given the outcome of my inquiry I find the word “client” problematic as it infers a power dynamic. A client is one who seeks professional services, reinforcing the idea that learned experience is of higher value. Another common term, “stakeholders,” didn’t feel specific enough—after all, there are many stakeholders in an organization. Overall, we’ve found it challenging to appropriately convey the relationship in a way that honors those who bring the lived experience and work collaboratively with an organization. If you have terminology you’ve found effective, feel free to comment below!

[2] For more on how to use feedback to create community-centered services, see Can You Hear Us Now? Using Feedback to Create Community-Centered Services!

[3] For more, check out the work of Community Centric Fundraising, a fundraising model that is grounded in equity and social justice.

[4] Want to learn more about trust-based leadership? Check out Brené Brown’s Dare to Lead!

[5] For example, Vu Le describes a model that involves seeking feedback from those most directly impacted before making any decision. While this isn’t necessarily shared decision-making, it does effectively center the people served and impacted.

Youth Feedback (as described in Finding #4 above):

Nourishment: Some agreed there is not enough for every teen to receive a food and drink serving. Garage staff will make sure to keep refilling food and look into expanding hot food options.

Sign 2 says: Quiet Space: We received an ask for more quiet spaces…a reminder that you can reserve the conference room or hang out in the counselor’s office when not in use. Ask a garage staff member to see if either room is available!

Sign 3 says: Sustainability: We are also looking into more sustainable dishware and silverware options to reduce waste! Thank you for your suggestions.

If you’d like to share more about your feedback, please reach out to a staff member in person.

Leave a note in the suggestion box, or email [email address]. Thank you!

You might also like:

- Vision Before Strategy: A Nonprofit’s Guide to Defining Success

- Hedging Your Bets: Rajiv Shah, and the Limits of Large-Scale Changemaking

- Unlocking Potential: Collective Leadership in Nonprofits

- From Crisis to Clarity: Five Steps to Demystify Succession Planning

- The Expanded Matrix Map: Leveraging Your Triple Bottom Line for Fundraising

You made it to the end! Please share this article!

Let’s help other nonprofit leaders succeed! Consider sharing this article with your friends and colleagues via email or social media.

About the Author

Gail Rothman is a dynamic, visionary, and entrepreneurial leader with over 20 years of nonprofit leadership experience. She loves to coach and support executive directors and boards who want to increase their impact and engage more deeply with their community. Her areas of interest include establishing and executing organizational vision, creating and growing new revenue channels, building organizational capacity, developing high impact programs and teams, and facilitating board development and engagement. She currently serves as a Senior Consultant with The Callahan Collaborative, a full-service nonprofit consulting firm.

Gail joined The Callahan Collaborative after serving as the executive director of the Decatur Education Foundation for 14 years where she was known for her authentic leadership style and willingness to tackle the hardest issues facing youth in her community. Under her leadership, the foundation developed programs to close the opportunity gap based on family income, led behavioral health initiatives (including the creation of holistic mental health centers at the local high and middle schools), and helped incubate other community organizations and programs to strengthen the services offered to youth.

Articles on Blue Avocado do not provide legal representation or legal advice and should not be used as a substitute for advice or legal counsel. Blue Avocado provides space for the nonprofit sector to express new ideas. The opinions and views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect or imply the opinions or views of Blue Avocado, its publisher, or affiliated organizations. Blue Avocado, its publisher, and affiliated organizations are not liable for website visitors’ use of the content on Blue Avocado nor for visitors’ decisions about using the Blue Avocado website.

At the Youth Sentencing & Reentry Project we are committed to the term “client partner” to remind everyone that YSRP is centered on the agency and dignity of those we serve.

I love that!