Strategic Planning 101 for Nonprofits: Strengthen a Nonprofit’s Board-Executive Director Relationship

A step-by-step guide to refocusing the board-executive director relationship to better align with their nonprofit’s greater mission.

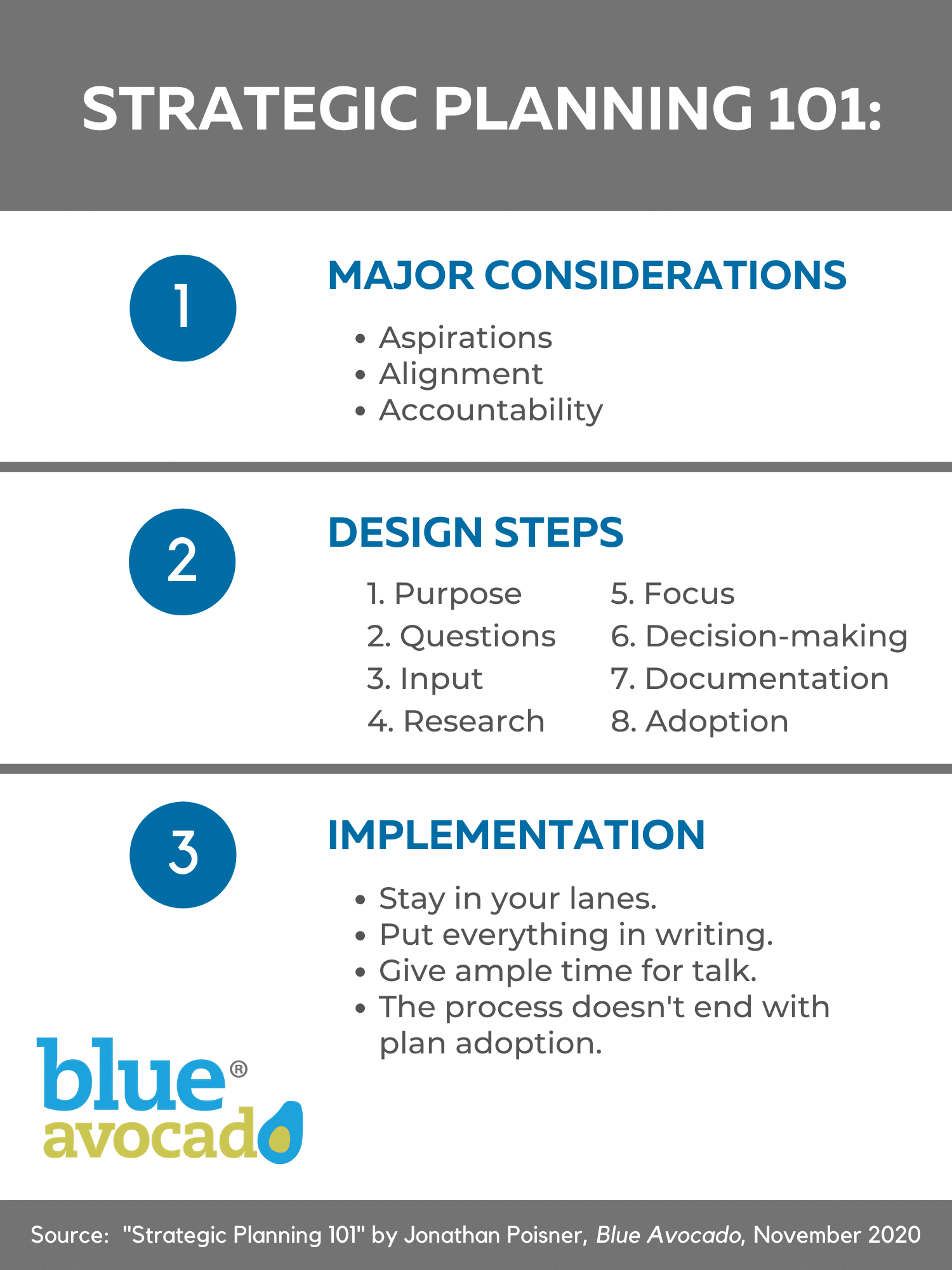

Follow the three A’s: Aspirations, Alignment, and Accountability.

When I talk to nonprofit leaders about strategic planning, they often voice some of the obvious benefits of aligning teams around organizational identity (mission, vision) and organizational priorities (goals).

In contrast, they rarely voice a benefit I think is undervalued: The opportunity strategic planning presents for a board and executive director to strengthen their relationship.

The board-executive director relationship is critical to a thriving nonprofit. A poor relationship can create unnecessary friction that diverts time and energy away from the mission and other institutional challenges. Conversely, the complete absence of disagreement can signal a disengaged board, which carries its own obvious risks. This article provides a step-by-step guide to begin to realign the board-executive director relationship with a nonprofit’s greater mission.

Major Consideration Before You Start: The Three A’s

Strategic planning can be a relationship-building tool from the perspective of three A’s: Aspirations, Alignment, and Accountability.

Aspirations: Strategic planning processes done well should include some effort to help participants get in touch with the underlying aspirations that drive their participation. In a nutshell: What does the organization aspire to accomplish? Aspirations can be at the abstract level of a mission and vision or the more concrete level of goals and objectives.

Your organization may already be in alignment on your vision and mission, and you may mostly need a planning process to drill down into strategies and measurements of success, or some other specific organizational challenge.

As such, you may be tempted to skip any conversation that could uncover your vision. Sometimes that’s appropriate, but it’s often a mistake. Make sure that board members and the executive director can hear (or read) each other talking about the big-picture aspirations that motivate their involvement. This shared dream-talk can help the group subsequently reach alignment when the talk turns to the more mundane world of strategy and evaluation.

A shared, motivating dream can help smooth things over when mundane differences appear—as they inevitably will in any organization.

Alignment: A good strategic plan lays out where the organization wants to get and how it will get there. By openly discussing and reaching agreement on these things—and putting that agreement in writing—the board and executive director can come into alignment. If the strategic plan identifies an evaluation process and that evaluation process is subsequently used to track progress and make adjustments, the odds the alignment will be durable increase. At a minimum, the evaluation process should include measurements of success with regard to strategic plan goals/objectives and clarity around who will track the data, how the data will be reported, and on what timetable.

Accountability: A good strategic plan doesn’t just lay out what you want to do, but also provides at least some clarity on who’s leading on what. Evaluating and supporting the chief executive is a core board responsibility. A well-prepared strategic plan can be a highly useful tool for the board in such evaluations.

A good strategic planning process should also incorporate at least some explicit areas where the board should lead. This could be limited to traditional areas of board engagement (board governance and recruitment, fundraising) or be more expansive (the board as ambassadors, board involvement in programmatic work, etc.). The board’s ability to hold itself accountable—such as via an annual self-evaluation—goes up markedly if the board and executive director have reached agreement via the strategic planning process regarding the top priorities for the board in the coming years.

Strategic Planning 101. Once major considerations are explored, work toward your vision with actionable steps. Then, take considerations to safeguard the strength and efficiency of the relationship during implementation.

The Initial Design of the Process

While every strategic planning process is different, the following eight-step process can be used to design the process in a way that accounts for the three A’s.

In applying this process, it’s critical to answer the questions in writing. It’s also essential to understand it as an iterative process in which you create an initial draft design and then test it against a set of questions before finalizing it.

Step 1: Purpose

What are the two or three most important reasons you are moving forward with a strategic planning process at this point?

Step 2: Questions

What (if any) big strategic questions or choices does the organization face that the planning process should help resolve?

Step 3: Input

Whose input (internally and externally) needs to be secured in order to help inform the answers to the big strategic questions/choices?

Who will collect the input? How? By when? How will the input be shared?

Step 4: Research

What other factual information needs to be developed in order to inform the answers to the big strategic questions/choices? Who will collect this information? By when? How will the information be shared?

Step 5: Focus

Who will decide what questions/topics need to be discussed and answered by the full board/staff leadership in light of the input and research compiled? When?

Step 6: Decision-making

Who will deliberate to address the questions/topics? When? By what decision-making process?

Step 7: Documentation

Who will document the discussion/decision and who will produce the draft strategic plan? By when? Who will comment on it and what process will be used to move from draft to a version ready for potential adoption?

Step 8: Adoption

Who will vote on adoption? When?

Testing against the Three A’s and Redesigning

Before finalizing the timeline and process you will use to develop your strategic plan, test whether a tentative process matches up with the three A’s, using a template such as the following:

Aspiration: At what points during the process will participants be able to voice their aspirations and hear each other’s vision?

Alignment: At what points during the process will decisions be made? How will those decisions be put in writing?

Accountability: In what step in the planning process will it be determined who leads on what? Will the planning process provide for clarity as to how/where the board should be prioritizing the board’s time during strategic plan implementation?

After answering these questions, edit the process draft to address any concerns identified.

Implementation Considerations

As you begin to implement the process, there are four other important considerations to keep in mind that can be important for the board-executive director relationship.

Stay in your lanes.

A healthy board-executive director relationship depends on a mutual understanding of their respective areas of responsibility and areas of shared responsibility. Strategic planning is an example of a shared board-executive director responsibility. If the process is either too staff-controlled or too board-controlled, it can lead to problems.

Put everything in writing.

The preference for documenting the process in writing should carry over with implementation of the process as designed. Miscommunication can be a big challenge for the board-executive director relationship and written communications are more likely to prevent miscommunication than talk.

That means promptly circulating notes from key meetings. It means making sure that everyone has time to comment on drafts and that the ultimate plan encompasses all the major decisions; or, if decisions are made that don’t wind up in the strategic plan, put them in some other accompanying document.

Give ample time for talk.

Not everyone’s focused on writing/reading, so make sure meetings themselves give room for discussion. Board members (and staff) are busy, so you may feel pressure to compress meeting times.

If possible, resist that urge and schedule meeting and retreat times so that there’s time to talk things through without being rushed. A rushed process is more likely to damage relationships as one or more participants may feel railroaded. A good facilitator can allow for shorter meetings to accomplish more, but even the best facilitator can’t deal with meeting times that are overly compressed.

The process doesn’t end with plan adoption.

Don’t fall into the trap of adopting a plan and then setting it aside. The first few months after a plan is adopted are critical to ensure that you will have a culture of accountability when it comes to plan implementation. The first couple of board meetings after a plan adoption should have an agenda item to report on and discuss early plan implementation.

Longer-term accountability depends on looking back at the plan. At least once a year, a board meeting should have as an agenda item a big-picture review of strategic plan progress.

Consider inserting these evaluation/implementation tasks into the strategic plan itself so as to increase the odds you’ll do them.

A good strategic planning process can’t take a bad board–executive director relationship and by itself fix the relationship. But if approached with intentionality, the process can be part of a resetting of expectations around communications and accountability. And if the relationship is already good, the planning process can reinforce the positive aspects of the relationship by providing an opportunity to dream together, talk together, and make and implement decisions together.

You might also like:

- Bylaws Checklist

- A Board Member “Contract”

- Can Nonprofit Boards Vote By Email?

- From Passive to Proactive: Strategies to Move Nonprofit Board Members Beyond Meetings and Into Action

- Four Ways to Remove a Board Member

You made it to the end! Please share this article!

Let’s help other nonprofit leaders succeed! Consider sharing this article with your friends and colleagues via email or social media.

About the Author

Jonathan Poisner (he/him/his) has over 25 years of experience in the nonprofit sector. Since fall 2009, Poisner has worked as an independent organizational development consultant, with a focus on strategic planning, fundraising, communications, coalition building, and other organizational development challenges. Based in Portland, Oregon, Poisner has served more than 90 clients in the Pacific Northwest and across the country. Prior to working as a consultant, Poisner spent a dozen years as Executive Director of the Oregon League of Conservation Voters. During this time, he served as a mentor helping launch and grow sister organizations in other states. Poisner is the author of Why Organizations Thrive: Lessons from the Front Lines for Nonprofit Executive Directors.

Articles on Blue Avocado do not provide legal representation or legal advice and should not be used as a substitute for advice or legal counsel. Blue Avocado provides space for the nonprofit sector to express new ideas. The opinions and views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect or imply the opinions or views of Blue Avocado, its publisher, or affiliated organizations. Blue Avocado, its publisher, and affiliated organizations are not liable for website visitors’ use of the content on Blue Avocado nor for visitors’ decisions about using the Blue Avocado website.