Why Are Nonprofits Experiencing An Insurance Crisis? And What Can the Nonprofit Sector Do About it?

Nonprofit organizations are facing rising insurance premiums, poor coverage from commercial insurance carriers, and the loss of coverage altogether. Going forward, it will be increasingly difficult for nonprofits to secure the insurance they need to keep their doors open. A visionary foundation could change all this, and benefit many tens of thousands of nonprofits for decades to come.

If you’re reading this, you probably already know about the problems that nonprofits like yours are facing with their insurance: Rising insurance premiums, poor coverage from commercial insurance carriers, and in some cases, the loss of coverage altogether. Many of these nonprofits have never made a claim. Going forward, it will be increasingly difficult for nonprofits to secure the insurance they require to keep their doors open.

Chances are, nobody’s ever explained to you the reason these problems exist, or the uncertain future that nonprofits face with their insurance.

In this article, I’ll explain all of this, and offer an elegant solution: A single investment that can help tens of thousands of nonprofits for decades to come, change the course of the entire nonprofit sector, and write history.

Why are insurance rates soaring for nonprofits?

With the exception of fire-prone areas related to property, nonprofits’ risks generally haven’t changed much over the past decade.

The problem is not a frequency issue: The number of claims received has not gone up. That is remarkably stable.

So why do insurance rates keep going up for nonprofits? The short answer: Opportunistic attorneys, social and financial inflation, climate change, limited options for reinsurance, and legacy claims from the COVID-19 era.

Nonprofits Insurance Alliance (NIA) is the nonprofits’ own insurer, with a 35-year track record of success. NIA, the tradename for a group of nonprofit insurers (all of whom are nonprofits themselves), has been able to moderate some of these premium increases over the short term. However, NIA will only be able to continue to help more nonprofits and have the necessary long-term stabilizing effect the nonprofit sector needs if it receives a large infusion of surplus to take it to scale.

What would that stabilization of insurance for nonprofits look like?

The answer is fourfold.

1. Lower liability insurance limits

First, the community-based nonprofit sector generally must carry lower limits of liability insurance. Those higher limits that have been required in the past are like catnip to plaintiff attorneys. It would be better if one or two nonprofits fail because of a large jury award, than the entire nonprofit sector lose its ability to be insured.

2. Reduce reliance on commercial reinsurance

Reinsurance can be thought of as insurance for insurance companies. Most insurance companies have reinsurance in order to protect their solvency and transfer a portion of their liability to the reinsurer. NIA is currently dependent on commercial reinsurance companies for their reinsurance.

To break this dependence, a large foundation, or a consortium of foundations, would make a significant investment in NIA to enable the sector to reduce reliance on commercial reinsurers for the first one or two million dollars of insurance limits. Otherwise, a larger and larger share of philanthropy’s donations and earnings from services will end up in shareholder pockets, rather than in service to our communities.

If NIA could provide coverage for the first two million dollars in limits without significant reliance on reinsurance, it would allow nonprofits themselves to determine which risks are acceptable, without any of the political or social action concerns that cause large public corporations to shy away from this business. Given the direction our present administration appears to be taking on DEI and other programs working toward a more equitable community, this is the only sane path toward sustainability.

3. Work to create a fairer judicial environment for nonprofits

NIA has been working for several years to help pass common-sense laws in the most problematic states to help level the playing field so that nonprofits are not being held accountable for things over which they have no control.

We have worked and/or are presently working on legislation with nonprofit associations in California, Texas, Pennsylvania, Illinois, and Florida. We were successful in helping to get a few provisions changed in Pennsylvania and California. These changes were helpful, but none of these bills passed in a form that meaningfully impacted the insurability of any group of nonprofits.

We continue to work on this for nonprofits generally, and also specifically for certain sectors, such as foster family agencies, that are not insurable under present law and judicial procedure.

4. Expand federal law to enable nonprofit insurers to diversify their risk portfolios

NIA is working with a constellation of nonprofits from across the country to allow a narrow amendment to a federal law, presently circulating as a discussion draft of the Nonprofit Property Protection Act (NPPA). The NPPA would enable insurance companies for 501(c)(3) nonprofits that are organized as risk retention groups (RRGs) to provide property insurance to their members in addition to the more complex liability risks they already insure.

For small and mid-sized nonprofits, the property insurance they need is not available from commercial insurance companies in a form that allows them to pair it with the liability insurance they get from their RRGs.

Further, allowing nonprofit RRGs to insure for property as well as liability would allow them to further diversify their risks across the country — gaining a similar reduction in overall risk to that of investing in stocks and bonds, and not just the more volatile stock market.

The property issue that the NPPA would solve is about to go from a problem to a full-blown crisis, since the single commercial insurer presently offering this coverage has indicated it plans to stop offering it in July of 2025.

How a one-time investment can change the entire nonprofit sector

Here’s a preview of the ask: As mentioned above, NIA is looking to gain independence from extensive reliance on commercial reinsurance companies, so that nonprofits themselves can determine the contours of the risks they can undertake without regard to profit for stockholders.

A one-time grant of $100 million from a foundation (or group of foundations) would help many tens of thousands for decades to come and help stabilize the wild gyrations we are seeing in the commercial insurance market.

This capital would allow NIA and the nonprofits they insure to circumvent the constraints of commercial reinsurance companies, for-profit companies that make decisions for shareholders and are influenced by political winds that may not be aligned with the needs of the social sector.

How did we get here?

We are currently in a situation where commercial insurers are nonrenewing nonprofits in droves and have been for several years. The main targets generally seem to be those nonprofits serving vulnerable populations, providing affordable housing, and social advocacy around equity for immigrants and minorities. The information below describes in more detail how we got here.

This has happened before

In the mid-1980s, a similar thing happened, and nonprofits were caught completely off-guard. Was nonprofit management suddenly failing to keep clients safe? Was training insufficient? Were nonprofits just really bad at taking care of vulnerable populations?

Back then, we had no idea what was happening. But some visionary foundations determined that, even if we can’t fully control the insurance marketplace as a sector, at least we needed to create an organization to help with the immediate problems and begin gathering data to understand what had transpired, in case this ever happened again.

It is happening again, but this time we know why it is happening. Nonprofits Insurance Alliance (NIA), the group of 501(c)(3) insurers enabled by those visionary foundations now exists, and this paper is based on what we have learned.

Why is this happening now?

There are several reasons — none of which are that nonprofits have somehow become riskier because they are not good at caring for vulnerable populations.

1. COVID-19

The start of this cascade of events began with COVID-19, with the impact being felt most strongly in California.

Many nonprofits continued to operate and provide essential direct services for the most vulnerable, but terminated top leadership and others since funds were short. Once the agencies with which to file grievances opened up and backlogs started clearing in the courts, those employees sued for wrongful termination.

As a result, insurers were flooded with employment practices lawsuits, many from nonprofits. While most of those claims have been resolved, the financial impact continues to reverberate through insurers’ bottom lines.

2. Social Inflation

Social inflation is occurring nationwide but varies in intensity by state. Plaintiff attorneys have learned that they can demand policy limits on nonprofits’ liability insurance for injured children or vulnerable populations — even when the nonprofit was not at fault — because judges will allow these cases to be brought. Juries will award huge sums without regard to damages or the culpability of the nonprofit.

Enraged by the cover-ups of abuse by large institutions and inflamed by plaintiff attorneys, juries are transferring that rage with a desire to “teach those companies a lesson,” even if that company happens to be a small nonprofit that was not negligent.

With a few notable exceptions, we’ve already shown that the frequency of claims against nonprofits has not increased — but the damages awarded have exploded with nuclear verdicts.

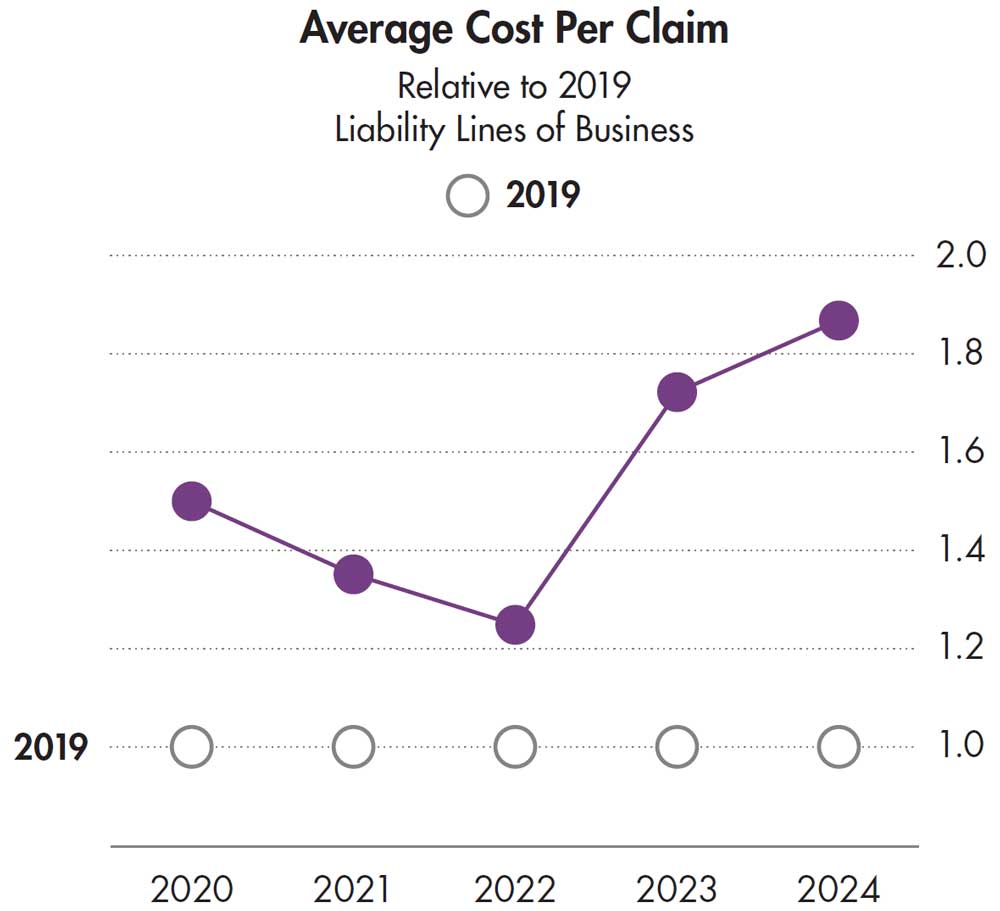

The chart below illustrates the average cost per to settle claims at from 2020 to 2024 relative to those received in 2019. The dip from 2021-2022 was related to less activity stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The claims we are seeing with more frequency relate to California employment practices, because of the specifics of employment law in that state.

We are also seeing an increase in the frequency of habitability claims for affordable housing in many states. The practices of affordable housing providers have not changed, but the willingness of juries to award large damages has.

As soon as these providers can make repairs to facilities, the tenants begin their destruction of the premises — letting sinks overflow, ripping out toilets, knocking holes in the walls, to name just a few. Then, despite the nonprofits’ efforts to fix these problems, an enterprising attorney finds 20 or 30 tenants and files habitability claims.

These attorneys go from one location to another, often filing claims over and over again for the same issues — making themselves rich and destroying the capacity to provide affordable housing.

Nearly all types of nonprofits serving vulnerable populations have seen a significant increase in the cost of handling claims. Even if the frequency is flat or down, the inability to use the civil justice system to protect nonprofits that have not caused harm is resulting in large, negotiated settlements because the risk of getting nuclear verdicts is so great if these cases are taken through to a jury trial.

Take, for example, a recent claim involving a foster child.

The foster family agencies did not and could not have known that a prospective foster father would become an abuser. He had been a foster father many times and had many children of his own, all who vouched for his being a great father. He had never abused before. All of the background checks were clear.

During this placement, either the government agency overseeing this child or the foster family agency was in the foster home the equivalent of every other day. No concerns were raised.

The government agency testified that the foster family agency had complied with every aspect of the verification and oversight process.

A jury still awarded more than $10 million against the foster family agency because, as one of the jurors said, “We know the foster family agency didn’t do anything wrong, but we felt sorry for the child.”

This is not insurable.

Other examples involve teens that run away while staying in group homes.

Even though the nonprofit may not prevent the child from leaving the facility, and even if they try to follow the child and report the elopement to the police immediately, juries still award large sums — even to parents who had told the child never to return to their home again.

These are tragic cases, but the nonprofits should not be held responsible if they meet the standards of care.

Other cases involve adults in independent living facilities that chose to take drugs against house policy. When they die or are gravely injured from an overdose, juries are sympathetic and award large sums to their families, even if there was nothing the nonprofit could have done since they have no control over the activities of the adult. Examples like this are legion.

For decades, we have successfully insured against negligence and wrongdoing by nonprofits with great success. But, in this new era, there is little or no consideration of whether the nonprofit was the cause of the injury. If someone is hurt, the nonprofit named in the lawsuit is expected to pay.

3. Financial Inflation

Health care costs impact the costs of slip-and-fall and auto accidents. It costs more to repair automobiles and the people who travel in them.

Even modest medical bills of less than $50,000 can now draw demands from plaintiff attorneys of $1 million or more for non-economic damages. The rise in obesity and co-morbidities create eggshell plaintiffs who generate large medical bills from even low-impact accidents.

While we are typically successful at getting the amounts of auto claims more in line with actual damages, these cases still have the potential for nuclear verdicts and typically result in settlements noticeably larger than in the past.

For claims that are more difficult on which to place a value, such as allegations of abuse, the range of awards can vary even more dramatically.

4. Climate Change

Nonprofits cannot escape the impact of the climate crisis on the cost and availability of insurance. Properties located in high-risk areas have few options outside of state-provided markets of last resort, such as FAIR Plan insurance. Even nonprofits not in high-risk areas can face nonrenewal of policies as carriers leave entire states.

While NIA cannot solve the problems created for property insurance by climate change, it can create a more stable and reliable market for the vast majority of nonprofits who do not have buildings with large property values and who are not located in high-risk areas.

5. Contraction in the Reinsurance Market

This contraction of the reinsurance market is a direct result of the other causes listed in this article, but its impact on insurers is exacerbated by two things:

- There are only a few reinsurers that will even consider providing reinsurance capacity at the levels needed by small and mid-sized insurers like NIA. Hence, when one or two reinsurers decide to step away from reinsuring this sector, it has an outsize impact.

- Reinsurers do not need to give any notice of nonrenewal or change in policy terms. While insurers like NIA must provide quotes in advance and give long notice of nonrenewal, reinsurers have no such requirements and can leave carriers exposed for business written many months before reinsurers have provided their renewal terms and conditions.

Many of the nonprofits that have been cast off from commercial insurers or those that NIA are presently unable to help end up in the surplus lines market — which is typically reserved for large, unusual, or emerging risks.

These carriers have become the last resort for desperate nonprofits: Companies can charge exceedingly high premiums and dictate whatever terms and conditions in their policies to limit coverage. They offer policies requiring that claims are made during the year the policy is in force and then can nonrenew those policies at any time, leaving the nonprofit with no coverage for those prior policy years — even if they have paid premiums amounting to many multiples of what they had been used to paying in the past.

What can be done to soften the cost of all this for nonprofits?

There are several things that are already being done to help moderate this difficult situation. Some can be done by NIA, and others require support from the nonprofit sector — including foundations — across the country.

What is NIA doing to moderate the crisis facing nonprofits?

As nonprofits’ own insurer and a 501(c)(3) nonprofit itself, NIA’s sole mission to provide insurance capacity and risk management to other 501(c)(3) nonprofits.

Presently, 27,000 nonprofits rely on NIA. Having doubled in size since COVID-19 hit, NIA has tried to be the safety net for as many nonprofits as possible.

The five issues listed above have had their own impacts on NIA, and although some are frustrated that NIA has not been able to hold costs and limits of coverage steady, we are doing everything possible to moderate the crisis facing nonprofits.

1. Lowering insurance policy limits available to nonprofits.

The nonprofit sector must reduce its available limits of insurance to incentive the plaintiff attorneys to focus their rapacious behavior on other industries.

It may be counterintuitive for nonprofits and their insurance brokers, but by lowering limits, this disincentivizes the plaintiff attorneys from focusing on this sector.

Counties and other funding sources have exacerbated this problem of large awards against nonprofits by demanding higher and higher limits of insurance in their contract with nonprofits.

The commercial insurance carriers that participated in this escalation by offering increasingly higher limits of insurance were the first ones to nonrenew when claims started coming in, leaving nonprofits with contract requirements for insurance coverage they could not meet.

Despite this constant demand for higher and higher insurance policy limits, it has been our experience that we are able to handle claims of all types within much lower policy limits, and these higher limits only paint a target on the nonprofit. The same set of circumstances can settle for $1 million, if that is the limit of the policy, that would demand $10 million simply because that happens to be the policy limit.

The way to stop this escalation of settlements untethered to actual damages is to lower available insurance policy limits. Counties and other funders need to recognize this. In our experience, plaintiff attorneys do not go through the additional work of suing nonprofits to get additional damages in excess of policy limits. They take the available insurance and move on.

2. Increasing premiums in relation to the changed risk.

NIA has used our extensive database to develop target premium increases required because of the factors driving settlement cost increases.

Whenever possible, we make increases in increments over several years to allow nonprofits’ budgets to catch up.

Our goal is financial stability for NIA and the nonprofit sector, not shareholder profits. But we must have sufficient funds to pay claims.

3. Shifting to claims-made policies for the most volatile of risks.

NIA has offered policies for social services professional, sexual abuse, and employment practices on an event-trigger or occurrence policy form for many years, because we wanted to provide the assurance of continuous coverage afforded by those policies.

But the dramatic shifts in the judicial climate no longer allow us to offer those policies as frequently as we would like.

For many types of nonprofits, we must revert to claims-made policies that allow us to make adjustments to rates and policy forms once the data can be analyzed at the end of each year. This will also help keep the cost for these coverages down for most nonprofits.

4. Reducing nonprofits’ own insurers from their overreliance on reinsurance.

Insurance rating agencies and regulators require insurance companies to hold a specified amount of capital (also known as surplus) for the risks they undertake when they issue insurance policies.

The levels of surplus are determined by complicated formulas that depend on the type of business written, the exposure rates, and the growth rate of the insurer, as well as other considerations, such as the amount of risk taken on a net basis by the insurer.

The amount of free surplus relative to the risk undertaken is key to determining how much reinsurance an insurance carrier must purchase. The higher the reliance on reinsurance, the more that insurers’ fates are tied to the erratic nature of the commercial reinsurance market.

One significant step that national foundations could do to reduce NIA’s reliance on commercial reinsurance would be to provide surplus support. That would mean making a significant grant of capital (surplus) to allow nonprofits’ own insurer to take on more risk net of reinsurance.

In short, our nonprofit member insureds and their own insurer, NIA, are being buffeted by dramatic changes to their environment.

At least this time, we know from our data that the frequency of claims against nonprofits, particularly for liability, is generally not the problem.

That doesn’t make the problem less challenging for nonprofits, their insurers, or their insurance brokers. However, we are in a much better position to know the steps that must be taken to provide correction.

In addition to the steps NIA has already taken to lower its risk profile while still providing the insurance this sector needs, what options does the nonprofit sector as a whole have to address this problem?

As described above, one controllable reason for the instability of this situation for nonprofits relates to reinsurance capacity and the amount of reliance that nonprofits’ own insurers have on the reinsurance market.

Reinsurers tend to be most comfortable reinsuring companies that take a large portion of each risk themselves. But small and mid-sized companies such as NIA, with just shy of $250 million in surplus, are limited in the risk they are able to take by the amount of their free capital/surplus. Companies with more surplus have much stronger negotiating ability in the reinsurance market.

Presently, large amounts of grant donations are going to pay for higher and higher insurance costs, much of that driven by the cost of reinsurance.

A single grant that could help tens of thousands of nonprofits for decades to come

However, if a large foundation or group of foundations would make a significant grant —of the magnitude of $100 million — it would assure that, in the decades to come, it is nonprofits themselves that are making the decisions about what are tolerable risks, without having to accede to the demands of the reinsurance market, whose decisions for their shareholders and political winds may not be aligned with the needs of the social sector. Putting this amount into perspective, NIA presently writes premiums of $350 million. If nonprofits are forced into expensive commercial solutions, often double or triple what NIA is able to offer, that means a potential transfer of $350 million to even $700 million in premium dollars, when a significant addition to NIA surplus would allow those funds to stay in the nonprofit sector and used as leverage on their behalf.

Over its 35-year history, NIA is one of the few 501(c)(3) financial institutions that has demonstrated that it is fully capable of being self-sustaining and growing its equity to keep up with its normal growth.

However, faced with the headwinds of the changing civil justice system and the abandonment by many commercial insurers of the nonprofit sector, NIA will be able to continue successfully with modest growth, but will be limited in the number of nonprofits it can help without a significant infusion of surplus.

We would expect this to be a one-time infusion and that the plans now in motion to sufficiently curtail risk will allow NIA to move forward in its normal self-sustaining manner.

Without this investment, some nonprofits will either have to go uninsured or continue to have to rely on a few surplus carriers which use their near-monopoly power to provide stripped-down policies at extremely high costs, directly transferring to their shareholders’ funds that could and should be used for social programs.

In many cases, the nonprofits will need to shut down entirely or shed the services the commercial insurance sector is unwilling to insure.

A solution is at hand, if the visionaries come forward.

You might also like:

- Rethinking Perpetuity: Resetting Endowment Expectations After the Pandemic

- Risk Management for Nonprofits: Copyright

- Don’t Let Internal Controls Slip at Your Nonprofit Organization!

- Five Emergency “Musts” for Your Nonprofit

- Sarbanes-Oxley and Nonprofits: Bogeyman in the Boardroom?

You made it to the end! Please share this article!

Let’s help other nonprofit leaders succeed! Consider sharing this article with your friends and colleagues via email or social media.

About the Author

Pamela Davis is the founder, president, and CEO of an affiliated group of nonprofit insurers known as Nonprofits Insurance Alliance® (NIA), the publisher of Blue Avocado. Pamela has grown NIA from a loan of $1 million from a group of foundations to over $314 million in premiums and $874 million in assets as of 2023, serving over 27,000 nonprofits across the country. All NIA affiliates are 501(c)(3) nonprofits, just like the organizations that they insure, and all NIA assets belong to the community, just like they should! Follow her on Twitter @pamela_e_davis

Articles on Blue Avocado do not provide legal representation or legal advice and should not be used as a substitute for advice or legal counsel. Blue Avocado provides space for the nonprofit sector to express new ideas. The opinions and views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect or imply the opinions or views of Blue Avocado, its publisher, or affiliated organizations. Blue Avocado, its publisher, and affiliated organizations are not liable for website visitors’ use of the content on Blue Avocado nor for visitors’ decisions about using the Blue Avocado website.